Lori Shubert and her company Cupcake Sushi, LLC filed an interesting lawsuit against Santiago and his associates doing business as Sushi Sweets, for patent infringement, trademark infringement, misappropriation of trade secrets, common law trademark infringement, federal and state unfair competition, and trade dress infringement. Shubert claims to have invented a unique confectionery dessert cake:  cupcake sushi. Shubert has apparently built a thriving business in Key West Florida. According to the complaint, Santiago, a former licensee and employee of Cupcake Sushi, absconded with product, equipment and Cupcake Sushi’s trade secrets.

cupcake sushi. Shubert has apparently built a thriving business in Key West Florida. According to the complaint, Santiago, a former licensee and employee of Cupcake Sushi, absconded with product, equipment and Cupcake Sushi’s trade secrets.

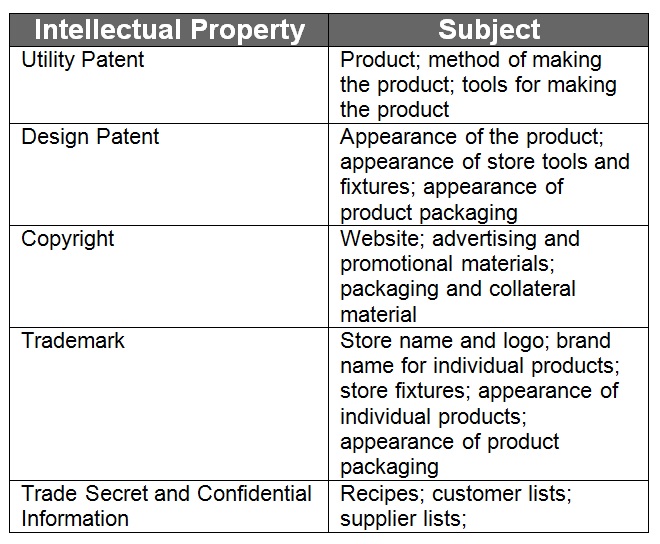

Shubert clearly had an interesting and appealing idea, and while she took some steps to protect it, she probably should have formed a more comprehensive plan at the outset. As she pleads in her lawsuit she applied for a utility patent (14/487364), she allowed the application to abandon. She also applied for and obtained a design patent (D789,025) but filed the application several years after she claims to have developed her product. Even if this patent validly protects a later design, she left her earlier designs exposed. While she did register her CUPCAKE SUSHI name and logo (Reg. Nos. 4471750 and 4770652), she might have also tried to protect her products names and appearances.

Resources are always tight in start-ups, and it is easy to second guess the allocation (or lack thereof) to lawyers, as entrepreneurs always seem to have other fish to fry. Shubert probably could have done more and done it sooner. Shubert did take a number of appropriate steps to protect herself, and if those rights have been violated, then hopefully she will be able to enforce them and this won’t represent the fish that got away. However, a more comprehensive approach might have made enforcement like shooting fish in a barrel:

Shubert may have learned another important lesson about protecting confidential information. A confidentiality agreement does not make a dishonest person honest. The most important steps in protecting confidential information is limiting disclosures to people who can be trusted.

Shubert may have to also have to face the fact that no matter how comprehensive your intellectual property protection, there will always be some way for other to compete. Good luck to Ms. Shubert, but if things don’t work out, there are always other fish in the sea.