Lawyer’s strive for perfection in their , but time constraints, budgets, and other factors work against us. Also, perfection is not always the same thing in every circumstance. It is interesting, however, to contemplate, what perfection might look like

1. Confidentiality

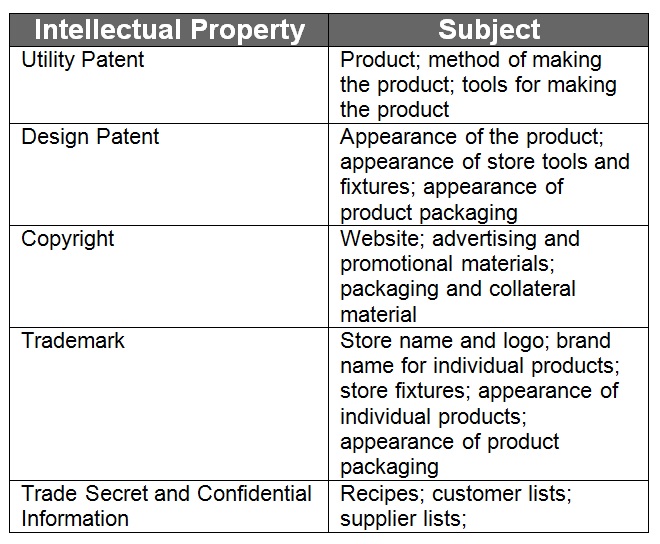

One of the primary purposes of an employee agreement is to protect the confidential information of the employer, as well as the employers suppliers and customers. The agreement should obligate the employee to protect all confidential information that the employee reasonable knows the employer regards as confidential, regardless of whether the information is marked confidential.

2. Non-Compete

While in some jurisdictions it may be possible to get an injunction against an former employee from competing with the former employer where it is inevitable that the former employee will disclose or use the former employer’s trade secrets, generally the only way to stop a former employee from competing is with a specific covenant not to compete. Even with such a covenant, the protection is usually limited to instances where the departing employee had access to trade secrets or had contacts with customers.

While current employees cannot complete with their employer, they are generally permitted to prepare to compete. However such preparation is something that an employer might be able to restrict by contract, for example requiring an employee refrain from making preparations to compete with the employer while still employed, or preventing an employee from working with current or former employees in preparing to compete with the employer while still employed. The employer should also consider requiring employees to report any breach of the non-compete provisions, so that it gets timely notice of problems.

To facilitate enforcement of a covenant not to compete, the employer might require the employee to keep the employer advised of subsequent employers. The employer should further obtain a consent of the employee to contact subsequent employers to advise them about their new employees obligations to the former employer. Otherwise, the employer could face a claim of tortious interference from the former employee.

3. Non-Solicitation

It’s bad enough when an employer loses a critical employee, but losing a group of employees can be devastating. This can be addressed in part with carefully crafted covenant not to compete. However, an employee can agree not to solicit his/her co-workers to work for a competitor,

4. Assignment of Inventions

Aside from confidentiality, the critical function of employee agreements is to transfer employee inventions to the employer, The agreement should require the employee to promptly disclose new inventions to the employer. The agreement should also include a promise to assign inventions, as well as a present assignment of inventions. Employers should be careful, however, because some states restrict the inventions that an employer can require an employee inventor to assign.

The employer should include a specific consent by the employee to file a patent application on any invention made by the employee during the term of employment. The employer should also consider an agreement not to contest any patents that are obtained. While the courts generally won’t entertain such attacks because of assignor estoppel, but the Patent Office will allow inventors to attack the patent through inter partes review.

To protect against the situation where an inventor is unwilling or unable to execute a subsequent assignment document, the employer might include a power of attorney, so that an officer can execute assignment document on behalf of the employee.

Particularly where an employee has a history of inventing, the employer should consider requiring new employees to identify previously made inventions that the new employee may claim do not belong to the inventor.

While copyrightable works prepared by employees in the scope of their employment are works-made-for-hire that belong to the employer, works prepared by employees outside the scope of their employment — even if they relate to the employer’s business — belong to the employee. An employee agreement can of course change this result, and the employer should ensure that it obtains ownership or at least the right to use all of the works of its employees that relate to the business.

5. Access to Computers

The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (can corresponding state laws) provides some protection from disloyal employee’s misuse of the employer’s computer systems and data. However, this protection hinges on whether or not the employee’s access to the computer system and data was authorized. Since most employees are on some level authorized users. it is important for an employer to define what access is authorized, and what access is not.

6. Return of Employer Property and Confidential Information

The Employer should specifically require the return of any employer property and information by a specific date. The failure of a departing employee to do so is surprisingly common, and gives the employer legal leverage over the departing employee.

7. Publicity and Social Media Restrictions

Employee names and likenesses are often incorporated into the employer’s marketing, and the employer would prefer not to have to rework these materials every time an employee departs. Thus, an employer should obtain the express consent of employees to use their names and likenesses in promoting the employer, and this consent should survive the termination of the employee’s employment.

For employees that are active on social media, the employer should consider imposing some restrictions on employee conduct on social media. The employer might require that employees not associate the employer with their personal posts. The employer might also require that the employee not comment about the employer, or at least comment negatively about the employer.

Occasionally, whether by design or by accident, an employee who is active on social medial becomes the official or unofficial voice of the employer. The employer needs to consider what happens to the employer’s social medial presence when this employee leaves. Does the employer get to take over the account? Does the employer have the user name and password?

Checklist

- Recitation of Consideration

- No impact on Status of Employment at Will

- Confidentiality

- Protects Company information and that of customers and suppliers from disclosure or use.

- Regardless of whether marked “confidential.”

- Prevents export of information (if appropriate).

- Promise not to disclose confidential information of previous employers and other third parties

- Covenant to Not-to-Compete

- Appropriately limited in geographic scope or time.

- Protects confidential information and/or customer contacts.

- Includes preparations to compete while employed.

- Competition/Competitors clearly defined.

- Guaranteed period of non-competition.

- Obligation to advise employer of subsequent employment

- Consent for employer to contact subsequent employers

- Non-Solicitation

- Appropriately limited to key personnel

- Appropriately limited as to duration

- Assignment of Inventions

- Appropriate definition of invention (consistent with state law).

- Requirement of prompt disclosure (of all inventions including those not subject to obligation to assign).

- Automatic, immediate assignment of inventions when made, as well as a promise to assign inventions.

- Power of attorney to execute confirmatory assignment on behalf of employee.

- Authorization to file patent applications on assigned inventions

- Identification of prior inventions not subject to assignment,

- Treatment of inventions made in period after termination of employment.

- Assignment of copyrightable works.

- Agreement to execute further documents to secure and enforce rights in assigned inventions

- Promise not to challenge validity of patents on assigned inventions

- Access to computers and data

- Access limited to activities that solely benefit employer and no other purpose.

- Acknowledgement that accessing computer system or data for any purpose other than for the benefit of the company is unauthorized.

- Acknowledgment of and consent to monitoring of computer usage, email, and company resources.

- Return of Employer Property

- Obligation to return all employer property

- Obligation to return/delete all employer data from personal computers and other electronic devices

- Obligation to turn over or destroy all physical and electronic files containing information belonging to employer

- Publicity and Social Media

- Consent to use name and image in advertising and promotion, even after the employee leaves.

- Restrictions on references to employer on social media, including in usernames or scree images on any social media.

- Requirement to turn over login information for any social media accounts officially or unofficially associated with employer.

- Representations from Employee

- Free to accept employment

- Not under any covenant not to compete (or identification of existing covenants)

- Not under any confidentiality agreement (or identification of existing agreements)

- “Boiler Plate” Provisions

- Choice of law.

- Choice of forum.

- Non waiver.

- Modifications must be in writing.

- Duplicates and Facsimiles of Agreement are effective.

- Integration.